by André de Waal and Kettie Chipeta

- Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to determine whether there are common conceptions of high performance organizations (HPOs) among business in South Africa and Tanzania. This is important to know because their perceptions will not only influence the nature and scope of topics, syllabi and course materials used in teaching, but will also influence the priority of organizational decisions which are going to be made by the students when they are managers.

- Design/methodology/approach – Data were collected by means of a questionnaire from a sample of 357 second and third year business students who were asked to rate the 35 items contained in the HPO Framework (Waal, 2012) on a seven-point Likert-scale.

- Findings – Factor analysis revealed that South African and Tanzania business students put priority on three of the original five HPO factors: continuous improvement and renewal, long-term orientation, high quality management, comprising 16 of the original 35 HPO characteristics. A bi-variate correlation between the HPO factors and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions revealed a significant relationship between the HPO factor long-term orientation and three of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, for both cultures.

- Originality/value – The value of the study is that it adds to the HPO literature by focusing on cultural implications and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. The answer to the research question are there similarities or differences among business students from South Africa and Tanzania in their perceptions of what the priority should be in regard to strengthening specific characteristics in the HPO Framework? is affirmative: yes, there are differences in high performance priority-setting per country and these differences can be explained by cultural differences. The findings of this study thus form a basis for the understanding of the effects of national cultures on the creation of HPOs.

- Keywords – South Africa, Tanzania, High performance organizations, Business students, National cultures, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

- Paper type – Research paper

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, research into the concept of the high performance organization (HPO) has enjoyed continuing interest (McFarland, 2008; Hensmans et al., 2013; Park et al., 2013). This is because being an HPO − which is defined as an organization that achieves financial and non-financial results that are exceedingly better than those of its peer group over a period of time of five years or more, by focusing in a disciplined way on what really matters to the organization (de Waal, 2012a) − is seen as away not only to survive but to thrive in difficult economic circumstances. Scholars and consultants have derived various theories of high performance and organizational effectiveness through close analysis of successful businesses and their practices. For example, Weber (1906, in Allied Consultants Europe (ACE), 2005) in his Scientific Management Theory emphasized the importance of organizational structure and processes; Drucker and Van de Ven (in Wren, 2005) emphasized aligning employee behavior to organizational strategy (in ACE, 2005; Wren, 2005); while Deming (1986, in ACE, 2005; Wren, 2005) emphasized the need of measuring people, processes and outcomes.

A recently developed HPO Framework is the one by de Waal (2012a, b) who spent ten years studying excellent, mediocre and bad organizations around the world. The HPO Framework (see the Appendix) was developed based on a review of 290 academic and practitioner publications on high performance and organizational effectiveness and a survey administered to organizations worldwide. The framework was subsequently validated for various Asian (de Waal et al., 2009; de Waal and Frijns, 2011; de Waal and Haas, 2013; de Waal and Tan Akaraborworn, 2013), African (de Waal and Chachage, 2011; de Waal et al., 2014), North-American (de Waal, 2012a), European (de Waal, 2012a) and Middle Eastern (de Waal and Sultan, 2012) countries. Studies in both western and non-western societies have shown the implications of different cultures for organizational structures, operations and performance (Aluko, 2003). Hofstede (1980) showed that national culture may affect managerial behavior, by influencing managers to support organizational values that are in conformity with the basic assumptions and beliefs they acquire and develop in their particular cultural contexts. However, the aforementioned validation studies of the HPO Framework seem to indicate the framework is generically valid in multiple contexts. The explanation for this apparent contradiction is that the HPO Framework indicates what is important for organizations to improve in order to become HPO, while it does not give ways how to improve the what. Thus, the what is generic valid while the how depends on the cultural context. For example, the HPO characteristic “Management is trusted by employees” is valid in every context as management which is not trusted cannot be effective no matter what the circumstances are. However, how management obtains and keeps the trust of employees could, and probably will, differ depending on the cultural context. So the HPO Framework indicates what the characteristics are an organization needs to strengthen in order to become highly effective and thus high performing (Richard et al., 2009), while it does not gives a “recipe” how to strengthen these characteristics, nor does it indicate in which order the characteristics need to be strengthened. Thus, there is also a question whether the priority of addressing the HPO characteristics is context dependent. This issue of priority-setting is a relevant one as an increasing number or organizations have a multi-national workforce with different cultural backgrounds. If there are cultural differences which can appear during the process of priority-setting, choosing which HPO characteristics to work on first can give ample opportunity for misunderstandings as the HPO Framework contains 35 characteristics. This is not an academic matter as Zwi and Mills (1995) described differences between developed and developing countries in choosing priorities regarding health policies, and Fink and Meierewert (2004) found cultural differences in priority-setting between West European managers and Eastern European managers while deciding on which tasks should be performed first. The study described in this paperis an attempt to evaluate whether priority-setting in relation to the HPO Framework is context dependent. It does this by investigating whether there are common views or differences among business students from different cultures on what they conceive to be the priority among characteristics in the HPO Framework. Specifically, the study tries to answer the research question:

RQ1. Are there similarities or differences among business students from South Africa and Tanzania in their perceptions of what the priority should be in regard to strengthening specific characteristics in the HPO Framework?

The reason for using business students as the research population was threefold. First, it is a matter of convenience. A class setting makes it possible to get a relatively homogeneous population (e.g. people who are about the same age and have the same interests and goals, in the case obtaining an MBA) which has one main differentiating trait (e.g. nationality). Second, business students are people undergoing training in order to become business leaders of the future. As such, their perceptions regarding the priority in HPO characteristics will have a significant influence on how future businesses will be shaped. Third, sampling only students in business programs enhances cross-cultural comparability by effectively controlling for important variables such as literacy and work experience (Muller and Thomas, 2001).

This study aims to fill a research gap concerning how (future) managers will in practice use an HPO Framework to give direction to their future improvement actions at their organizations. The study also contributes to the literature by shedding light on the issue whether priority-setting is culture dependent. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we present the literature review and in Section 3 the research methodology. The empirical findings are reported and discussed in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively, while the conclusion, limitations of the study and opportunities for further research are given in Section 6.

2. Theoretical background

In this section, overviews are given of Waal’s HPO Framework, the concept of culture and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Subsequently, the relation between culture and the HPO Framework is discussed, and the section ends with a treatise on the influence of culture on management in South Africa and Tanzania.

2.1 The HPO Framework

The HPO Framework was developed based on a literature review of 290 studies into high performance, organizational effectiveness and excellence and a survey administered to organizations worldwide (de Waal, 2006/2010, 2012a). In the literature review, for each of the 290 studies, elements that the authors indicated as being important for achieving high performance and organizational effectiveness were identified and categorized. Because different authors used different terminologies, similar elements were put in the same category. The resulting categories were labeled “potential HPO characteristic”. For each of the potential HPO characteristics the “weighted importance” was calculated, i.e. the number of times that it occurred in the examined studies. Finally, the characteristics with the highest weighted importance were considered the HPO characteristics. These characteristics were subsequently included in an HPO survey, which was administered worldwide encompassing over 3,200 respondents. In this survey, the respondents were asked to indicate how well they thought their organizations were performing as to the HPO characteristics (on a scale of 1 to 10) and also how the results of the organization they worked at compared to those of peer groups. By performing a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, 35 characteristics, which had the strongest correlation with organizational performance, were extracted and identified as the HPO characteristics. The resulting correlation was as expected: the high-performing organizations scored higher on the 35 HPO characteristics than the lower performing organizations. A principal component analysis with oblimin rotation was performed on the 35 characteristics, which resulted in five distinct HPO factors with sufficient high Cronbach’s α.

The HPO Framework consists of the following five HPO factors (de Waal, 2012a):

- Management quality: belief and trust in others and fair treatment are encouraged in an HPO. Managers are trustworthy, live with integrity, show commitment, enthusiasm and respect, and have a decisive, action-focused decision-making style. Management holds people accountable for their results by maintaining clear accountability for performance. Values and strategy are communicated throughout the organization, so everyone knows and embraces these.

- Openness and action-orientation: an HPO has an open culture, which means that management values the opinions of employees and involves them in important organizational processes. Making mistakes is allowed and is regarded as an opportunity to learn. Employees spend a lot of time on dialogue, knowledge exchange and learning, to develop new ideas aimed at increasing

their performance and make the organization performance-driven. Managers are personally involved in experimenting thereby fostering an environment of change in the organization. - Long-term orientation: an HPO grows through partnerships with suppliers and customers, so long-term commitment is extended to all stakeholders. High potential internal candidates fill vacancies first, and people are encouraged to become leaders. An HPO creates a safe and secure workplace (both physical and mental), and dismisses employees only as a last resort.

- Continuous improvement and renewal: an HPO compensates for dying strategies by renewing them and making them unique. The organization continuously improves, simplifies and aligns its processes and innovates its products and services, creating new sources of competitive advantage to respond to market developments. Furthermore, the HPO manages its core competences efficiently, and sources out non-core competences.

- Workforce quality: an HPO assembles and recruits a diverse and complementary management team and workforce with maximum work flexibility. The workforce is trained to be resilient and flexible. They are encouraged to develop their skills to accomplish extraordinary results and are held responsible for their performance, as a result of which creativity is increased, leading to better results.

The HPO Framework has subsequently been empirically validated in various countries by administering the questionnaire to organizations in a country and performing confirmatory factor analyses on the collected data. In each case, basically the same factors with underlying characteristics – or a subset of these – appeared (de Waal et al., 2009, 2014; de Waal and Chachage, 2011; de Waal and Frijns, 2011; de Waal, 2012a; de Waal and Sultan, 2012; de Waal and Haas, 2013; de Waal and Tan Akaraborworn, 2013).

2.2 Culture

2.3 Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

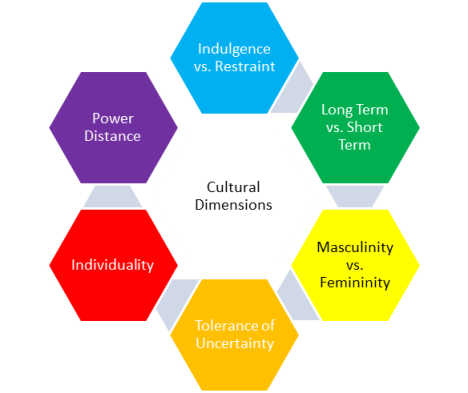

Hofstede (1980), in his research comprising 116,000 questionnaires which were completed by over 88,000 IBM employees in 72 countries, identified four bipolar cultural dimensions which have become a common basis of measurement of national culture (d’Iribarne, 1997; Dorfman and Howell, 1988; Schneider and Barsoux, 1997). In a later study Hofstede introduced a fifth dimensions, long/short term orientation, in an attempt to fit the uncertainty avoidance dimension into the Asian culture (Hofstede and Bond, 1984, 1988). However, this dimension has not been included in this research. The four original dimensions of national culture are described below:

- Power distance: this dimension measures the extent to which a less powerful individual accepts inequality in power. The degree of inequality that is tolerated by individuals varies from one culture to another. Individuals, in a nation that is characterized by high power distance, have a high degree of tolerance of power inequality: they accept that other individuals have more power over them. Because of this high tolerance of power inequality, they frequently seek guidance and direction from their superiors, and leaders are revered and obeyed as authorities. Organizations in high power distance culture have more levels of hierarchy, narrow span of control and centralized decision making.

- Individualism-collectivism: individualism describes the relationship between individuals and the group to which they belong or prefer to live and work in. Collectivism is the preference to work or live as a group rather than as an individual. A country with a high collectivist culture exhibits a high preference for group decision making. Consensus and cooperation is valued more than individual initiative and efforts. Motivation is derived from a sense of belonging, and rewards are based on group loyalty and tenure. A collectivist

society prefers to respect the group to which it belongs, usually the family. The role of leadership in such culture is to facilitate team effort and integration, foster a supportive atmosphere and create the necessary group culture (Beardwell and Holden, 2001). Markus and Kitayama (1991) suggest that individualism and collectivism are two independent dimensions, which should be split into vertical and horizontal sub-dimensions. However, to maintain consistency with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions original model, most scholars treat individualism and collectivism as extremes of a single dimension (Taras et al., 2010). - Uncertainty avoidance: this dimension relates to the creation of rules and structures to eliminate ambiguity in an organization and support beliefs promising certainty and protecting conformity. The implication is that people try in numerous ways to avoid uncertainty in their lives by controlling their environment through predictable ways of working. Organizations in cultures that score high in uncertainty avoidance show more formalization, as evident in greater number of written rules and procedures as well as greater specialization evident in the importance attached to technical competence. In countries that score high in uncertainty avoidance, people tend to show more nervous energy, while in low score cultures people are more easy going. According to Hofstede (2001), uncertainty avoidance is not equivalent to risk avoidance: it does not describe an individuals’ willingness to take or avoid risk, but instead describes an individuals’ preferences for clear rules and guidance.

- Masculinity-femininity: this dimension pertains to behaviors and values that are either cooperative or competitive (Taormina, 2005). Masculinity is defined as the dominance of competitive values in a society such as assertiveness, performance driven and success. Femininity on the other hand relates to cooperative and/or tender values associated with females such as caring forquality of life, maintaining warm personal relationships, caring for the weak and maintaining solidarity. In a feminine culture, the role of leadership is to ensure shareholders are satisfied, employees’ well-being is safeguarded and social responsibility is promoted (Bartlett and Ghoshal, 2000). Organizations ranking high on the masculinity management style are concerned with task accomplishment rather than nurturing social relationships.

2.4 Relationship between the HPO Framework and culture

In this section, the relation between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and the HPO Framework is discussed.

2.4.1 Power distance and HPO. In high power distance cultures, the role of the leader is stressed more strongly and the number of hierarchical levels is larger than in low power distance cultures (Blunt, 1988; Gupta, 2011; Hofstede, 2001; Largrosen, 2002). In this culture, empowerment and participative decision making are discouraged (Flynn and Saladin, 2001) and managers are seen to communicate less with their subordinates about the strategy and results of the organization (Snell and Hui, 2000). The large number of hierarchical levels prohibits employees from spontaneously and independently developing systematic improvement approaches, because subordinates first need to seek the approval of their managers (Lillrank et al., 2001; Snell and Hui, 2000). In addition, interactions and discussions with stakeholders at various levels, to build strong personal relationships, are hampered (Flynn and Saladin, 2001).

In contrast, in low power distance cultures employees have more freedom to use their own discretion (Gelfand et al., 2007) and to facilitate effective and efficient decision making at lower levels of the organization. Significant emphasis is placed on training subordinates on how to assume various roles (Largrosen, 2002), and employees have more….

For more information about the HPO Framework, HPO Experts, workshops and our do-it-yourself HPO Insight™ improvement tool, please contact us (schreurs@hpocenter.com or T. +31 (0) 35 – 603 70 07).